The Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the United States, recognized American independence and established borders for the new nation. After the British defeat at Yorktown, peace talks in Paris began in April 1782 between Richard Oswald representing Great Britain and the American Peace Commissioners Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Adams.

American Negotiators

The American negotiators were joined by Henry Laurens two days before the preliminary articles of peace were signed on November 30, 1782. The Treaty of Paris, formally ending the war, was not signed until September 3, 1783. The Continental Congress, which was temporarily situated in Annapolis, Maryland, at the time, ratified the Treaty of Paris on January 14, 1784.

On January 20, 1783 – England signs a preliminary peace treaty with France and Spain. On February 3, 1783 – Spain recognizes the United States of America, followed later by Sweden, Denmark, and Russia. On February 4, 1783 – England officially declares an end to hostilities in America.

On July 8, 1783 – The Supreme Court of Massachusetts abolishes slavery in that state. On September 3, 1783 – The Treaty of Paris is signed by the United States and Great Britain. Congress will ratify the treaty on January 14, 1784. On October 7, 1783 – In Virginia, the House of Burgesses grants freedom to slaves who served in the Continental Army. On November 2, 1783 – George Washington delivers his farewell address to his army. The next day, remaining troops are discharged.

The American Revolutionary War

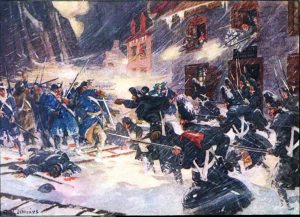

The American Revolutionary War (also known as the American War of Independence and American Revolution) was a war fought between the British Crown and its colonies in North America, allied with France, from 1775 to 1783. The eventual outcome was the recognition of the independence of the 13 southernmost of the colonies, as well as lightly settled territories west to the Mississippi River.

1783 was pre-eminently the turning-point in the development of political society in the western hemisphere. Though small in their mere dimensions, the events in a remarkable degree were germinal events, fraught with more tremendous alternatives of future welfare or misery for mankind than it is easy for the imagination to grasp.

As we now stand upon the threshold of that mighty future, in the light of which all events of the past are clearly destined to seem dwindled in dimensions and significant only in the ratio of their potency of causes; as we discern how large a part of that future must be the outcome of the creative work, for good or ill, of men of English speech.